Permitting and financing offshore wind projects is a complex business — but one that has made great strides on the East Coast of the United States in recent years. And it makes sense that the first wave of development has focused on high-load, transmission-constrained regions of the East Coast. High power prices, coupled with relatively shallow water depths and a generally supportive political climate, have made New York and New England the epicenter of the industry in the United States to date.

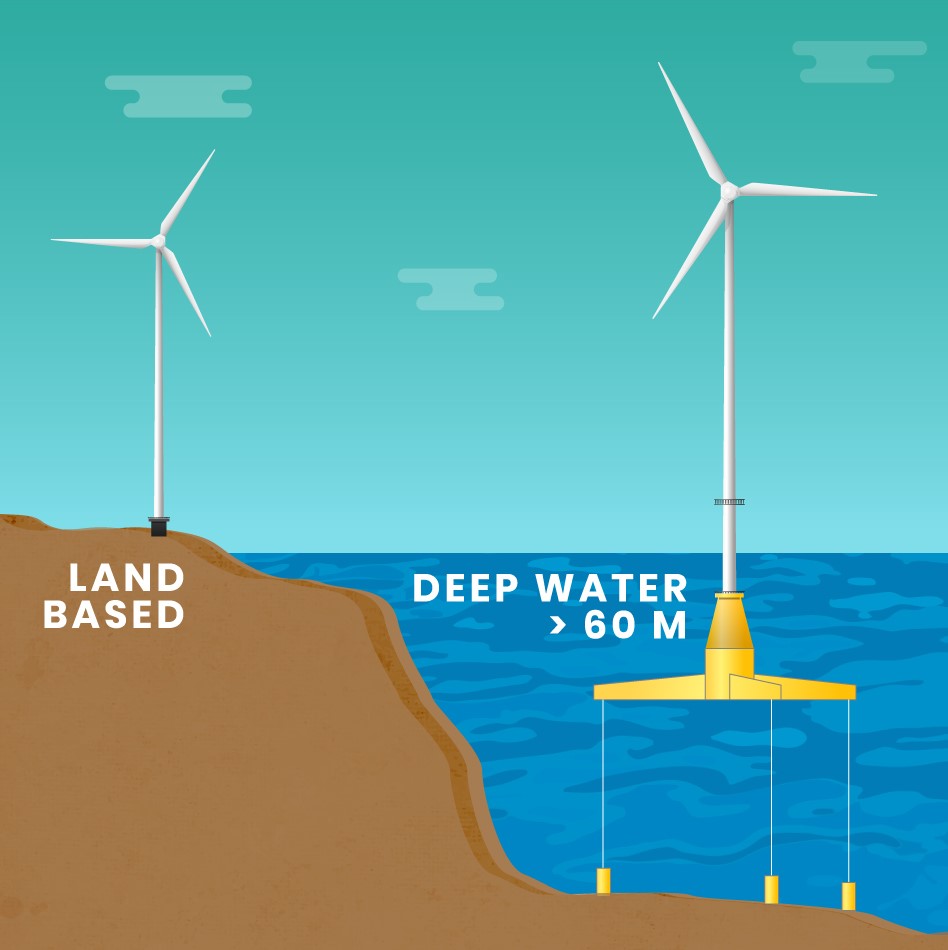

But make no mistake, the same offshore wind developers that are capitalizing on opportunities on the eastern seaboard have their eyes on California as the natural target for the second wave of U.S. development. As the world’s fifth-largest economy with a power-hungry population, an extensive coastline with strong winds, and a progressive legislature and governor, California is positioning itself to lead the offshore wind industry on the West Coast. That said, financial considerations (including tax credits), environmental regulations, and California’s unique permitting regime may offer new challenges to those who want to develop projects in its deep Pacific Ocean waters.

Financial Considerations

With both a relatively long timetable for offshore wind in California and a steep learning curve, the financing landscape is likely to change over time. Large balance sheet sponsors (as equity) and banks (as debt) — many of them from Europe — are expected to continue to dominate the field. However, the overall capital stack that sponsors have looked to in financing onshore projects over the last decade will almost certainly evolve over the next five to 10 years. For example, the production tax credit (PTC) and the investment tax credit (ITC) will have expired — possibly, without renewal. Even if one or both is eventually renewed, traditional tax equity that has fueled the growth of terrestrial wind in the United States generally represents a 12- to 18-month forward market. Since California offshore wind projects are still on the drawing board and will likely require construction periods of two years or more, it is premature to assume what role tax equity will play (if any).

For now, the safe assumption is that California offshore wind will not be able to rely on the same federal tax credits that have accounted for a substantial portion (typically 40 percent to 50 percent) of terrestrial wind financing. Indeed, turbine manufacturers continue to increase the size of their machines (e.g., GE Renewables’ announcement of its 12-MW Haliade X), and other components of the supply chain are similarly planning for the phase-out of federal tax credits. If developers of California offshore wind projects are able to use such tax credits, it is unclear whether they would represent a comparable percentage of the capital stack.

Without the PTC or ITC, the gap fillers will likely be term debt and equity partnerships akin to some of the recently announced joint ventures, such as Engie-EDP, Ørsted-Eversource, and EnBW North America-Trident Winds. Over a longer time horizon, as sponsors continue to understand and mitigate the novel development and operational risks facing floating offshore wind in California, it is also possible that private equity funds will begin to play a role in the overall financing picture.

Extension of the tax credits for offshore wind

Several groups are urging Congress to extend the ITC for offshore wind projects. Under current law, the ITC is available for wind projects (by election) only if construction begins on the project before 2020, which is an unattainable goal for offshore California development. Further, the full ITC (30 percent) is reduced by 20 percent for each year after 2016 that construction begins.

On June 25, 2019, the Offshore Wind Incentives for New Development Act (the Act) was introduced in both the U.S. Senate and the House of Representatives. The Act would extend the 30 percent ITC for projects where construction begins before January 1, 2026. Supporters of the Offshore Wind Act argue that, if passed, the Act would continue to incentivize offshore wind projects, which would, in turn, create jobs and address climate-control concerns. Moreover, they argue the expiration of the ITC will make offshore wind projects more expensive to develop and ultimately more expensive for energy consumers.

Passage of the Act is far from certain, however. It is clear that the Act will not pass as a freestanding bill; it will have to be included in a larger tax bill or, perhaps, a comprehensive budget and tax (omnibus) bill. In addition, with the 2020 presidential election approaching, passage of any major legislation before 2021 is politically problematic. Finally, the Act has drawn significant opposition, particularly from Sen. Charles Grassley, the chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. Grassley, who helped pass the original PTC more than 25 years ago, has indicated that he is prepared to allow the renewable energy tax credits to phase out as scheduled [1]. In 2015, Grassley advocated for an extension of the credits, pledging that the extension would be the last one.

California developers will no doubt keep a close eye on the potential extension of the tax credits for offshore wind, but they will be wise to take a conservative approach and prepare for a future without such tax credits.

Environmental Regulation and Permitting

California offshore wind projects will need regulatory approvals from a number of federal and state agencies charged with managing and protecting submerged lands and coastal resources, endangered and threatened species, marine mammals, cultural resources, water quality, and existing economically beneficial ocean uses such as crabbing, fishing, shipping, and recreation. To say the permitting process can have significant impacts on projects’ plans, development, and timing is an understatement. Developers will need to take a strategic approach to federal, state, and local permitting by understanding the approval process and requirements, knowing the most recent science on potential project impacts, and engaging resource agencies early regarding those impacts and potential mitigation measures. Patience is also advised.

Federal approvals

For successful offshore wind development, it will be important to work closely with a number of federal agencies.

The Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has jurisdiction over renewable projects located on the Outer Continental Shelf (OCS), the area three nautical miles from California’s coast. BOEM is responsible for granting leases, easements, and rights-of-way for renewable energy development activities, including the siting and construction of offshore wind projects on the OCS. BOEM’s competitive leasing program begins with the agency issuing a Request for Interest and involves multiple phases of public notice, development of site information, collection of information from potential developers, delineation of an appropriate lease area, analysis of potential environmental impacts under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and the holding of a lease sale auction. The winner of the lease submits a site assessment plan (SAP) for BOEM’s approval to allow for resource assessment and technology testing, and then a construction and operations plan (COP) describing proposed offshore wind facilities and construction and operation plans.

BOEM’s process for approving a COP involves multiple environmental and resource reviews. BOEM will review the site-specific plans under NEPA, which will include an opportunity for public review and comment. Depending on the potential for significant environmental impacts, BOEM may prepare an environmental assessment (EA) and a finding of no significant impact (FONSI), or it may proceed with the preparation of an environmental impact statement (EIS), a considerably longer and more detailed process.

BOEM must also consider the potential impact of its approvals on historic properties under the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) section 106 process. Through this process, BOEM or the developer, as BOEM’s representative, will consult with the state or tribal historic preservation officer and interested tribes to determine whether the project will affect any properties that are listed, or are eligible for listing, in the National Register of Historic Places. This process may result in an agreement on measures that the developer must take to avoid, minimize, or mitigate for any adverse effects. In most circumstances, BOEM will also conduct a “government-to-government” consultation with tribes.

Finally, BOEM will consult with the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) to confirm that construction and operation of the offshore wind project is not likely to jeopardize listed species or destroy or adversely modify their critical habitat. The developer may also be required to apply for and obtain an authorization under the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA) if the project is expected to harm whales, sea lions, or other marine mammals. This may be the case if, for example, NMFS believes the noise from the project may cause whales to move away from the project area. These ESA and MMPA consultation processes may take one year or more to complete, and may result in conditions being placed on the project to minimize any potential impacts to protected species.

Other federal agency approvals will also likely be required, depending on the project. For example, a United States Army Corps of Engineers approval under section 404 of the Clean Water Act will be required for any dredge or fill operations, including trenching for offshore cables or wetland fill that may be associated with onshore facilities. A United States Coast Guard Private Aid to Navigation Permit also will be necessary to ensure compliance with private and uniform aid marking requirements and to ensure waterway safety.

Additional federal approvals may be required if the project requires a right-of-way across a federal park, highway, or other federal lands. Federal agencies can generally rely on the environmental reviews conducted by the lead agency, here BOEM, under NEPA, ESA, NHPA and the Coastal Zone Management Act, and would not be required to conduct separate reviews.

State approvals

A number of California agencies can be expected to play a role in offshore wind development along the state’s 840-mile coast.

Under the California Coastal Act (Coastal Act), the Coastal Commission has jurisdiction over the “environmental and human-based resources of the California coast and ocean … for use by current and future generations.” [2]

The Coastal Commission regulates the development within the coastal zone (defined as offshore to the state’s jurisdictional boundaries and variable distances inland — sometimes as much as five miles) and affected local coastal communities. As with other offshore energy development industries, offshore wind is subject to the Coastal Commission’s authority to determine consistency with the Coastal Act.

The State Lands Commission is responsible for development and other operations over submerged public trust lands in the state. Typically, Commission jurisdiction is accountable for in-water projects such as docks, marinas, and ports, but approvals will also be required for onshore cables from offshore wind turbines that breach the shoreline. These facilities are subject to discretionary permitting in the form of fixed-term leases issued by the Coastal Commission and may be heavily conditioned to protect public access, including coastal access, and the natural environment.

The California Department of Fish & Wildlife administers the California Endangered Species Act (CESA) and will be called upon to determine whether any part of an offshore wind project affects threatened or endangered species or their habitat. Proponents are wise to understand the intricacies of CESA, including how it both complements and differs from the federal ESA, and whether incidental-take permits are required for state-listed species.

Finally, local agencies may have a hand in offshore development either through focused planning tools, such as Local Coastal Programs, or other onshore local permitting and approval processes. The extensive California coastline includes 76 cities and counties, each with its own regulatory scheme for review and permitting of onshore components. Careful scrutiny of the applicable local government’s codes and legislative enactments warrant close scrutiny as part of a project’s due diligence effort.

Discretionary actions by public agencies in California that may have a significant physical effect on the environment are subject to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). This can be in addition to the review described above under NEPA, though there are often opportunities for parallel and sometimes complementary processes. Wind developers must consider the substantial time and cost implications routinely associated with CEQA compliance. CEQA mandates public notice and participation and, when relevant, the mitigation or avoidance of potentially significant impacts. With the exception of the Coastal Commission, which is subject to an equivalent CEQA process known as a Certified Regulatory Program, each of the agencies identified must fully comply with CEQA before approving a project.

The way forward

California almost certainly will be the next hot spot for offshore wind development. As project sponsors move into California, they will need to carefully consider the financing, regulatory, and permitting issues that arise — some of which will be familiar and others that will be unique to the waters of the Pacific Coast.

References

- Ari Natter, “Democrats Try to Extend Wind, Solar Aid They Agreed to Let Die”, Bloomberg, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-05-15/democrats-try-to-extend-wind-solar-aid-they-agreed-to-let-die), May 15, 2019.

- Pub. Res. Code §30001.5.